“In Japan, there is a concept called Ikigai – which means, what is it that you want to do when you wake up this morning. My Ikigai is what I’m doing. It’s almost like finding your destiny. That’s what the music does.”

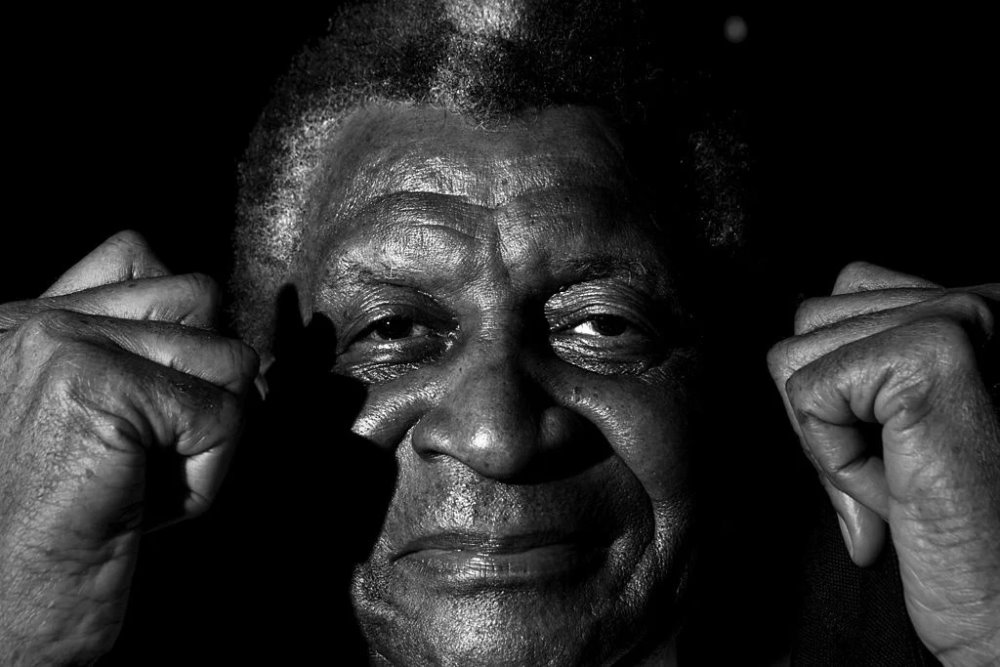

For respected pianist and composer, Abdullah Ibrahim, sound is central to his life-long exploration of spirituality, cosmology and memory. He first experienced sound through hymns in the church that his grandmother founded in Kensington, Cape Town. Encouraged by his grandmother, Ibrahim started playing the piano when he was seven years old.

Ibrahim says:

The thing that drew me to church every Sunday was the sound. In Islam, when I first heard the Qur’an being recited, it was the sound that touched me very deeply. I didn’t know what the words were, I discovered this after…And that’s what I found in the church; through the recital of the Qur’an; in the Green Kalahari with the San people and what I find in Japan at the Shinto shrine.

Ibrahim’s philosophy of sound is a nuanced marriage of ancestral understanding that spans the Kalahari where he is currently building a project, to Japan – a country for which he has a long-standing affinity.

Japan

In April, the 85-year old artist was awarded the prestigious 2020 Spring Imperial Decoration from the Japanese government.

He received the Order of the Rising Sun – an award which recognises his contribution to the emancipation of South Africa through music and celebrates his understanding of Japanese culture and spirituality.

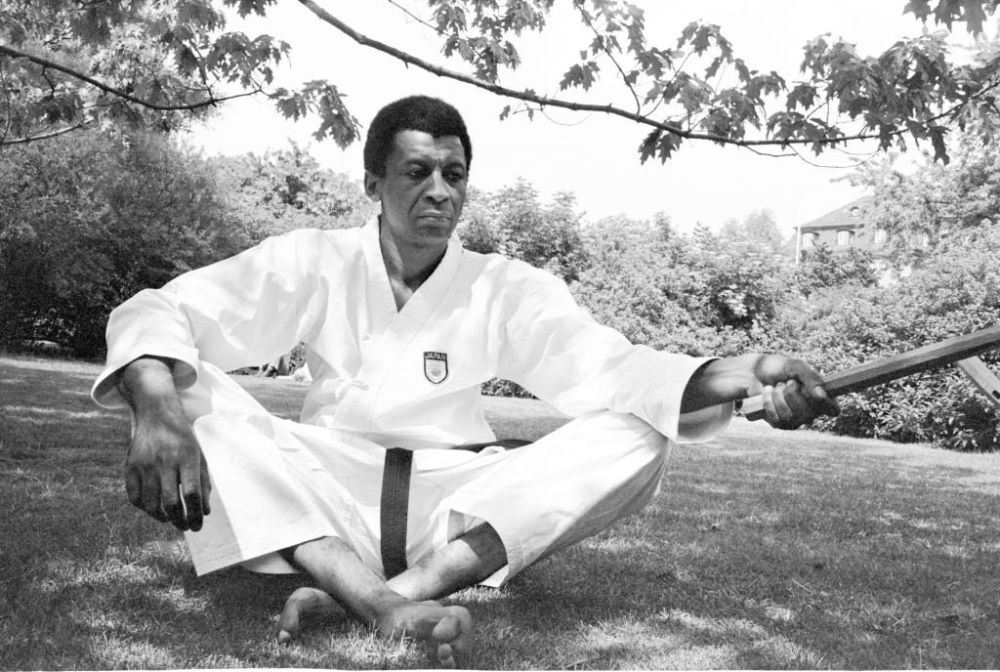

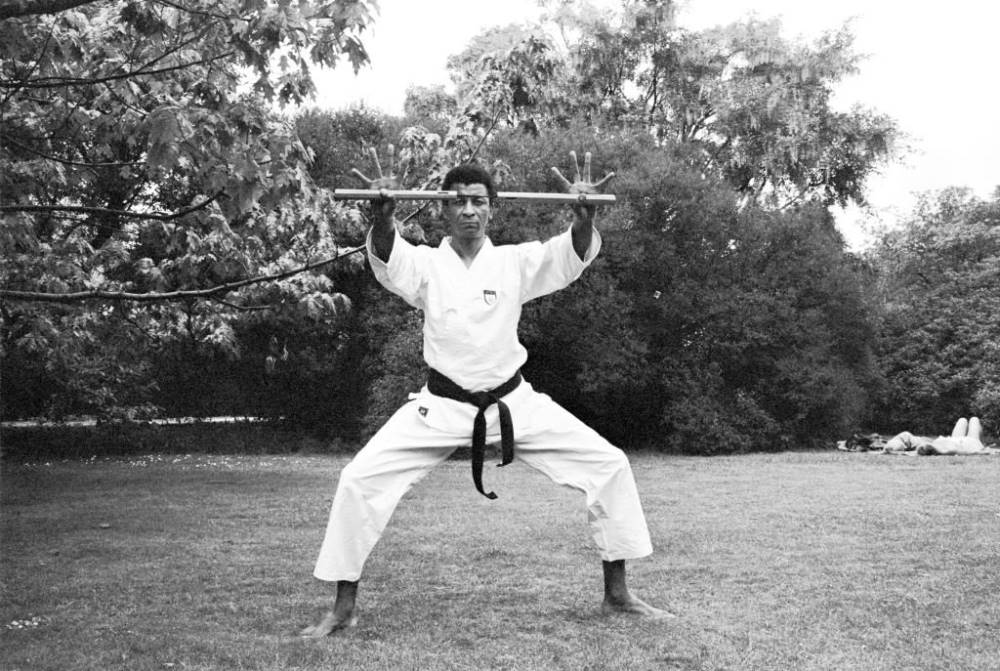

For the past 50 years, Ibrahim has been a dedicated student of Japanese martial arts, or budo, under his sensei grandmaster Yukio Tonegawa. He holds a black belt in karate. And he is a master-level teacher certified by Tonegawa, qualified to pass on this ancient form. Aside from performing many concerts in Japan over the decades, in 2008 he released Senzo – a solo piano suite whose title translates to “ancestor” in Japanese.

His 2014 album, Mukashi – Once Upon a Time is a quartet recording incorporating Japanese influences with stories from South Africa.

“We don’t do this to get accolades,” he explains. “When I was at high school, I was interested in alchemy and health issues. And then I was drawn to martial arts. At that time there was hardly anything really in Cape Town, so we studied our books. But I was always drawn to this concept. I have this unending appetite for knowledge. When I was in high school I went into the archives at the public library and I researched all the slaves that came to Cape Town – where they came from, what their names were.”

In 2018, Ibrahim would be approached by the Japanese Consulate in Cape Town to perform a concert marking the 100th anniversary of the Japan-South Africa relations. “Then the Consul asked me, ‘Do you know somebody called Antony Van Japan?’, and I said, ‘Yes, I know where his grave is’.”

Dating back to 1662, Anthony Van Japan was the first recorded person to arrive from Japan in South Africa – a slave who served Zacharias Wagenaer, Jan Van Riebeeck’s successor as commander of the Cape Colony.

“I told them where he is buried, at the Tana Baru cemetery in Bo-Kaap in Cape Town. That’s also where Tuan Guru is buried. Right? So there is this ongoing relationship with Japan.”

Tuan Guru was an Indonesian prince and scholar instrumental in bringing Islam to South Africa. He was exiled as a political prisoner to Robben Island in the 18th century, and is revered for transcribing the entire Qur’an from memory various times.

Ibrahim continues,

“And of course my studies in Japan with my teacher that is budo, is actually the same principle as the way that we play the music. There’s always anticipation, or something that is pre-emptive. Or you go into a dream state. So you play something that you’ve never played before and you don’t want to repeat anyway. At the heart of this, is something in Japan that is called S-A-T-O-Y-A-MA,” he says slowly, sounding the words out.

Satoyama Africa

Satoyama is the Japanese cosmology of conservation and biodiversity, creating a harmonious co-existence between humans and nature. Ibrahim is inspired by this Japanese philosophy for his project located on an 800-hectare farm in the Kalahari desert in the Northern Cape – under development for 25 years.

The intention is to include music, movement, medicine, meditation and Satoyama-biodiversity. The project engages the local community and neighbouring Botswana and Namibia.

“The idea is that we incorporate all of this. I call it Satoyama Africa which is this biodiversity with music, astrophysics and farm produce. For young people, the idea is to come there and engage in this. And for young musicians for example, composing in this dynamic. We have the ancient earth, and we have our sights beyond the milky way.”

In accordance with |Xam cosmology, the Milky Way was created when a little girl threw the ashes of a fire up into the sky, lighting the way for people on their way home at night. While origin stories of this nature were once common knowledge, the effects of colonisation resulted in many of these stories being untold and ultimately forgotten.

Stories like this, the need to remember them, is what pushes Ibrahim when he speaks about his plans for the farm and in the same breath refers back to his 1956 three-part composition written for Krotoa – a young Khoi woman who served as translator for 17th century Dutch colonisers.

Ibrahim acquired this immense capacity for ancestral knowledge from his great grandfather, who was a stable boy for Paul Kruger and fluent in various South African languages.

“He taught me all about herbs. Our cosmology stretches way, way back.” He adds excitedly: “One of the projects on the farm that we are working on that South Africans should visit is what we call the Wonder Cave – a cave that has got 2.5 million years of settlement and footprints. One of the oldest settlements in the world and we don’t know about it?”

The question is rhetorical. The answer is in the work.

The project echoes what the late musician and philosopher, Zim Ngqawana, created with his farm outside Johannesburg called the Zimology Institute, a place for learning beyond music. Ibrahim emphasises that when the project launches, the farm will be accessible for all to visit. “This is for everybody. We don’t regard ourselves as musicians, more special than anybody else.”

Last year, Ibrahim was the recipient for the National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters fellowship. He also released his latest album in five years, The Balance through Gearbox Records. Speaking from Germany, Ibrahim comments on life under the global pandemic.

“Well, we just continue what we normally do in our lives, see?” He laughs.

“Sometimes we think that people do not have a perspective of what it is that what we do and how we go about it. What people see is the one hour when we appear on stage. But that’s not it. See? That appearance on stage is 5%, the other 95% is practice at home. Our mode of living is always, as you’ve called it, under lockdown – to perfect what it is that we are doing.”

Ibrahim has taken this moment gently in his stride.

“You know in our lifestyle and our cosmology that has been passed on for generations by our elders and mentors, we must always be prepared for change. Because everything is in flux and everything is in change, and it comes back to its source. I think our understanding of this virus is that it is just a reminder for us, that we really should observe and re-evaluate what our role is in the universe. And especially in our immediate surroundings, right?”

Drawing inspiration from the sound of the trees, the wind and the birds, he says: “Even though I’ve spent times in cities, most of my life was spent outside of cities – in the mountains or in the deserts. Like the project that I have in the Northern Cape in the Kalahari. I think for us what this current situation does, is just make us understand that nature has a natural cause of events, as we can see now. Animals are coming into the cities. Thousands of dolphins are coming to the shores.”

He laughs: “So for us it’s just to understand what is our role and to re-assess ourselves and our relationships.”

*To celebrate Africa Month, Apple Music commissioned some of Africa’s finest artists (including Abdullah Ibrahim) to curate exclusive guest playlists made up of the biggest African songs of all time. Listen to the playlists here.