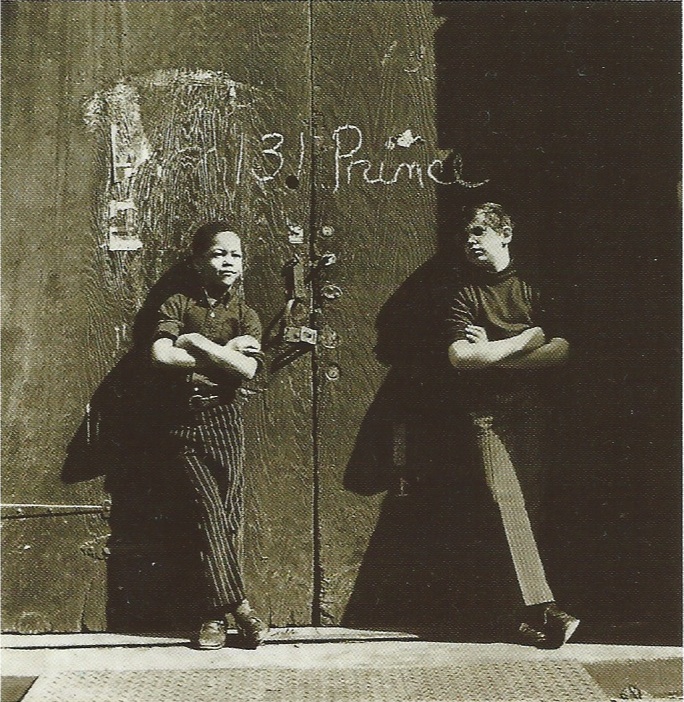

When I visited Ornette Coleman’s SoHo loft in early 1973, the threat of eviction was already hanging over him. The great saxophonist and composer had lived at 131 Prince Street since the late ’60s, when the district’s historic buildings had been under threat of demolition to make way for the proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway. Now the expressway scheme had been abandoned, and the neighbours were getting restless. They didn’t like the idea of jazz musician living in their midst, it was said. Particularly one who had turned his ground floor into a performance space, which he called Artists House. And real-estate agents were looking for a way of freeing up properties in a district whose beautiful but semi-derelict five-storey cast-iron buildings were about to make the transition from light industry to highly desirable residences and retail spaces.

The next SoHo loft I visited, on Greene Street in 1981, was occupied by David Byrne and Twyla Tharp, who had just collaborated on The Catherine Wheel, and the metamorphosis didn’t stop there. In 1999, Rupert Murdoch and his new wife, Wendi Deng, paid £6.5m for a triplex apartment at 141 Prince Street, five doors from Ornette’s old pad; six years later they sold it for almost $25m. For the last 20 years the streets have been lined with high-end clothes shops and expensive restaurants, and the sidewalks thronged with tourists. Like a lot of places into which developers and exploiters follow artists, SoHo lost its character on the path to prosperity.

One day in 1970, Ornette invited an audience of acquaintances and colleagues to attend a recording by his then-current quartet: Dewey Redman (tenor), Charlie Haden (bass) and Ed Blackwell (drums). The result was issued a couple of years later as an album called Friends and Neighbors on Flying Dutchman, a short-lived label run by the producer Bob Thiele, who had recorded Coleman (and John Coltrane and Albert Ayler) on Impulse in the ’60s. Now Ace Records in the UK has acquired the rights to Thiele’s catalogue, and Friends and Neighbors — which has always been hard to find, although I have a CD of the album reissued by BMG France a dozen years ago — is among the first releases. The photograph above, by Ray Ross, is from the cover.

The album starts in a rather eccentric fashion with the two short parts of the title piece, originally released — unlikely as it may seem — as a 45rpm single. On the first part, the audience chants a simple lyric based on the title, “Give Peace a Chance”-style, over a bouncy Blackwell second-line backbeat, either side of solos from Ornette’s screechy violin and Redman’s saxophone. The second part has no singing, and Ornette switches to alto saxophone; the groove persists, with Haden outstanding despite the murky sound.

The aural fog clears entirely for the remaining four pieces,all devoted to the quartet, among which the two extended tracks, “Long Time, No See” and “Tomorrow”, deserve to occupy an important place in Coleman’s discography. The intimacy of the interplay between alto and drums during Ornette’s six-minute solo on the former track is outstanding even by the standards of these particular players, with Blackwell giving a lesson in medium-up tempo swing. Ornette’s trumpet appears on the brief “Let’s Play” but he returns to the alto for “Forgotten Songs” and for “Tomorrow”, where the always underrated Redman leads off with a striking solo employing multiphonics and Ornette contributes another outstanding improvisation in collaboration with the endlessly stimulating rhythm team.

My visit to 131 Prince Street three years later yielded one of the most singular and intense musical experiences of my life. A group of half a dozen jazz writers from around the world were paying a visit to Coleman, who responded by inviting his house guest, the great pianist Abdullah Ibrahim, to play for them. If you’ll indulge me, here’s how I described it from memory a few years later, in the introduction to a book called Jazz: A Photographic Documentary:

The South African seated himself at the grand piano in the middle of the light, spacious loft while the visitors drew up their chairs in a semi-circle around him. He placed his hands together, bowed his head for a moment, and then he began. Perhaps he played for 10 minutes, perhaps for half an hour. Nobody in that room would have been able to say which.

He began with a hymn tune tune direct from the African Methodist Episcopal Church in which he worshipped and sang as a child; a slow, wise tune, its melody moving with a graceful inevitability, supported by simple harmonies that resonated with the richness of entire choirs. Then he changed gear, into a dance tune that moved to a swaying, sinuous beat and gathered momentum until it sounded like a whole township stepping out. Changing up again, his hands began to hammer great tremolos at both ends of the keyboard, the air in the room seeming to shimmer and the floor to shudder as his big fingers rolled harder and harder in a gigantic crescendo until suddenly bright treble splashes fell across the dark patterns like bursts of sunlight piercing a storm. Now pure energy took over, the melodies broken into abstract angular figures which leaped and tumbled and fought with a ferocious energy, bypassing the logic centres of the brain to reach some place that responds only to kinetic stimuli.

Just when it seemed that the intensity might burst the windows, Ibrahim backed off, returned to the double-handed tremolos, rewound slowly and with infinite care through the dance tune and the hymn, and deposited us back where he had found us, in silence — except that the silence now sounded completely different.

Soon after that Ornette was obliged to close Artists House. Around 1975, he was finally evicted altogether.

Richard Williams on July 8, 2013

thebluemoment.com/2013/07/08/131-prince-street/