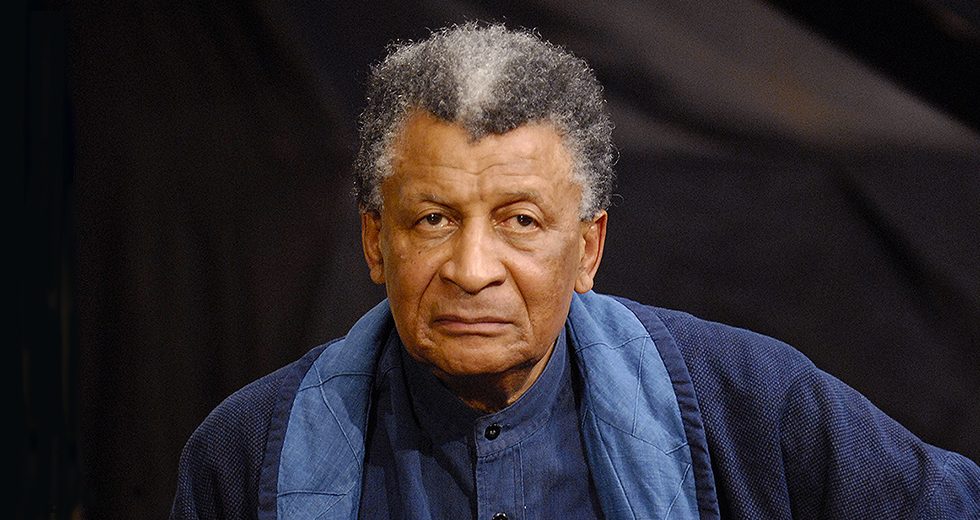

For more than six decades, South African jazz piano virtuoso Abdullah Ibrahim has delighted and enlightened audiences around the world. During his first years on the scene, Ibrahim (born Adolph Johannes Brand in Cape Town) kept company with giants like John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, as well as Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk. Coltrane and Coleman, whom he met in 1962, were especially significant influences on his musical style.

Now 85 and a recently minted NEA Jazz Master, Ibrahim is as busy as ever. When he drops by Symphony Center with his ensemble Ekaya on Feb. 28 — in the town where he fondly recalls gigging with drummer and Coltrane collaborator Elvin Jones during an early American tour — Ibrahim will play selections from his newest album, “The Balance.”

Writing about it in the New York Times last July, critic Giovanni Russonello described the record as “cooly disarming” and “arranged with a gentle touch.”

“Combining church hymns, South African marabi and post-modern jazz, Mr. Ibrahim doesn’t play with obvious ease of motion,” he wrote. “Instead he seems to hang back, suspending relief, beckoning you in.”

Shortly before doing so in Chicago, Ibrahim took some time to ruminate about his work and career. He is, to borrow a time-worn jazz term, one deep cat.

How have your musical taste, composition and style of playing evolved over the years?

There are millions of people, each with a unique voice unlike any other. My style is my own voice void of fashion current or past — a constant revision to enhance such — inspired by those before me.

Your newest album is called “The Balance.” Have you found balance in music and life? What does that mean?

The Balance is the joy of arriving after an arduous journey of self-discovery at a perceived goal and realizing that next and continuing road is just unfolding.

You’ve said you’re always “striving for perfection,” but what does actual perfection look like as you envision it?

We strive for unattainable perfection, with the understanding that there is no time frame to try to achieve it, anyway.

Finding the silence is a goal of yours but something that’s elusive in music as well as life. Why is silence so crucial?

I spent years searching for a sound before realizing that it was the illusive silence of serenity I was listening for. Our illustrious Rumi [a 13th-century Persian poet] said: “There is only one sound, everything else is echo.”

Nelson Mandela called you “our Mozart.” As you get older, does virtuosity on the piano give way to something even more rare and important?

What Nelson Mandela actually said after he came backstage at one of my concerts and responded to a question of how he felt about the performance, “Bach, Beethoven —we’ve got better.” I thanked Madiba [Mandela] immediately for that accolade, but I had already understood that he had actually, through his example, showed me that there is something beyond virtuosity.

What do you know about yourself now that you didn’t know early on, and how has that affected your music?

Self-discovery is a constantly expanding task. I invest in loss, channeling the ego productively.

You’ve said that jazz improvisation saved your life. Did you mean that literally? And how has it sustained your life since then?

Improvisation activates and has resonance in breath and memory. In our oral tradition, we preserve our cosmology through memory. It is a process of preparing to enter uncharted waters.

You practice martial arts. When did that begin, and how does it inform your music?

Traditional martial arts in Japan, “koryu budo,” resonates with our African concept of respect for all things: water, trees, people, self. It has nothing to do with fighting. The principle is that you strive to perfect what you do, not to challenge others but to make yourself unbeatable. Invest in loss.