Over the past few years, Abdullah Ibrahim (born Cape Town, South Africa, 9 October 1934) has shared his birthday with an enthusiastic audience in the Hirzinger Hall, Riedering, Germany. But in 2020 the circumstances around his 86th birthday gig changed. Owing to the pandemic, the audience was absent and Hirzinger Hall was empty except for a minimal recording crew. Ibrahim, unfazed, proceeded to do what he always does.

Begging the question: what does Ibrahim always do? Personal reminiscence follows: in the late 1950s, while he still answered to ‘Dollar Brand’, I first heard him at Cape Town’s City Hall, a rare unsegregated venue in apartheidSouth Africa. Local jazz stars performed their licks according to fashionable trends until it was Brand’s turn to appear at the keyboard.

During the late ‘50s, U.S. jazz was a beacon of freedom for many peoples oppressed by discrimination, injustice or persecution (in South Africa, if your skin wasn’t white, you were on the receiving end of all three) and thus a symbol of protest. Dollar Brand, a pianist equipped with formidable chops, immersed himself in the works of Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk and dedicated himself to follow their examples, placing honesty, passion, originality and personal experience at the centre of his art.

So, instead of recycling second-hand grooves from distant New York or Los Angeles, Brand opened his set with a delicate melody, stately and almost hymn-like, recognisably jazz, but subtly transformed. In the centre of this new music, the City Hall audience recognised a familiar flavour, an intense distillation of the vivid sounds that surrounded us. Because Dollar Brand was paying his tribute to the indomitable spirit and individuality of Cape Town and its citizens.

We Capetonians are justifiably proud of the Mother City that clings to the southern tip of Africa, dominated by magnificent mountains on a peninsula sculpted by currents of two competing oceans. Stiff breezes from Antarctica provide aircon in summer heat. The delicious wines, glistening beaches and powerful surf all intoxicate. Flat-topped Table Mountain, home to thousands of plants found nowhere else on earth, was regarded as a sacred site by the indigenous Khoisan population, a people older than time. It’s a vital city full of swagger, sardonic humour and overflowing with music. Yet, out on the windswept Cape Flats, the legacies of a racist regime persist: poverty, sorrow and resentment.

Brand/Ibrahim’s music, notable for moments of contemplation and traces of spirituality, encompasses it all: ancient Khoisan themes, Malay liturgy and yearning Cape Coloured gospel singing. Once, on a sultry Sunday evening in 1960, during an illegal multi-racial jam at Ambassadors, a dance studio on the outskirts of District Six (soft drinks and samosas. No booze on Sundays), Dollar Brand bewildered the audience by vacating the piano stool and offering it to his elderly auntie who stunned the young crowd with rolling gospel chords direct from the church. He wanted the white folks in the room to understand the roots of his music.

He’s a consummate storyteller whose beguiling tales and observations can be simultaneously tragic and upbeat, angry and celebratory, meditations on Cape Town’s heraldic Latin motto: ‘Spes Bona’ (which translates as ‘Good Hope’). Sadly, for many of us in 1961, supplies of ‘Good Hope’ had dwindled drastically, prompting mass exodus from our birthplace, Ibrahim included (but not before he’d joined trumpeter Hugh Masekela, alto-saxophonist Kippie Moeketsi and trombonist Jonas Gwanga to record ‘Jazz Epistles Verse 1’, South Africa’s finest jazz album). Once abroad, his recitals and recordings served to remind audiences of South Africa’s continuing struggle and us of our displacement.

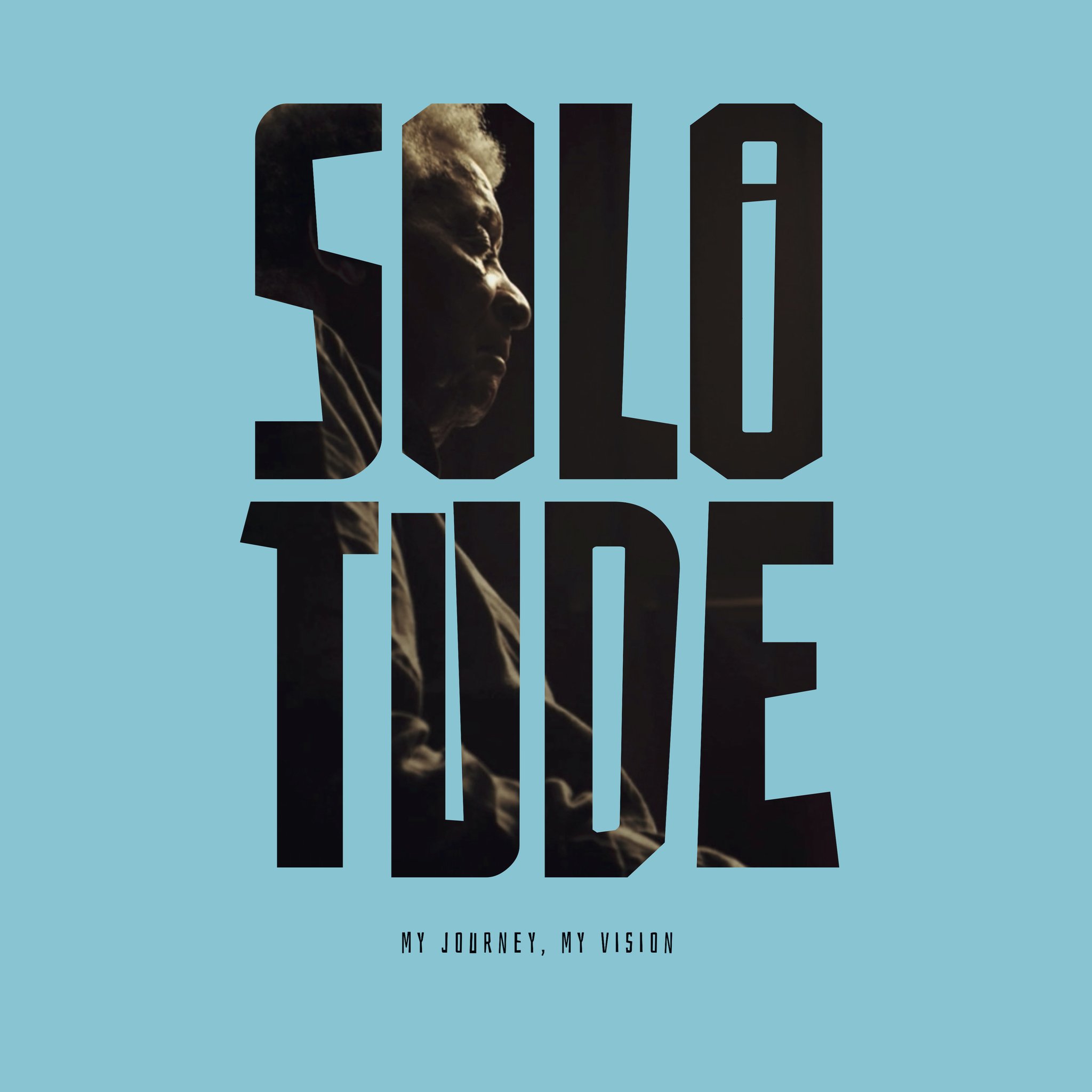

This latest album, the unaccompanied Solotude (subtitled “My Journey. My Vision”) from Hirzinger Hall, features 18 of his compositions and demonstrates what Ibrahim does, how he does it, the singularity of his genius and why he has attained legendary status. In 1994, when he performed at South Africa’s first post-apartheid presidential inauguration, Nelson Mandela described him as “South Africa’s Mozart”.

Now 87 years old, the venerable Ibrahim needs only to caress the keyboard for fellow Capetonians to identify the master’s touch and the source of his themes. Fortunately, for anyone unfamiliar with the Mother City, he provides clues. Three of Solotude’s tracks have specific Cape geographical references: Tokai, a sprawling mountainside forest adored for its peace and shade; the fabled District Six, once an urban quarter at the foot of Devil’s Peak where all races mingled (a fact that so infuriated the apartheid government that they brutally obliterated the entire area by official decree); and a new composition, the short and elegiac Signal On The Hill, citing Signal Hill, one of the four landmark mountains that cradle our city.

Be assured by this Capetonian that the rest of his repertoire couldn’t have come from anywhere else.

Or, for that matter, anyone else.

Solotude is released on 26 November 2021 – Bandcamp

Review by London Jazz News – read the original review here.