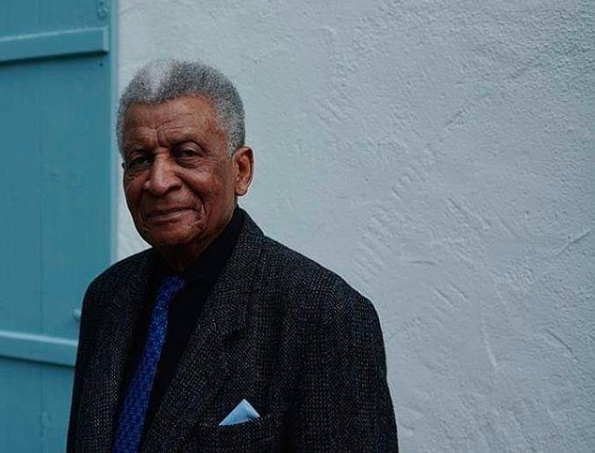

South African jazz pianist Abdullah Ibrahim is performing at the Berklee Performance Center on Saturday November 16th, presented by Celebrity Series of Boston. Al Davis and Va Lynda Robinson, hosts of Jazz on 89.7, spoke to him in advance of the show, reflecting on his roots in Cape Town, his formative years in New York, and his new trio.

Al Davis: Abdullah Ibrahim, welcome to Boston!

Abdullah Ibrahim: What an honor! Thank you so much.

Al Davis: You’re quite welcome. Tell us a little about the performance coming up on the 16th of November.

Abdullah Ibrahim: It’s a trio, with Cleave Guyton on alto flute and piccolo. Cleave Guyton is a journeyman, he was with [Duke] Ellington, and with Lionel Hampton. He comes from that wellspring of our tradition. We’ve been together for at least 40 years.

And we have a young man, Noah Jackson, on cello and bass. He’s a newcomer. It’s not the usual combination of bass drums and piano in this trio, but the format is a platform for all of us to broaden our core concept of the music without having to be anchored by a beat.

Va Lynda Robinson: I want to delve into history, if I may. You are considered a leading figure in Cape Jazz, but you grew up listening to Duke Ellington, and Thelonious Monk.

Abdullah Ibrahim: Yes, the latter part is correct. The first part, this idea of Cape Jazz… someone gave us that label, but we’re just musicians. But: Ellington and Monk. When I was in Cape Town, I used to listen to Ellington on a radio program, and some of the people in our community had some records. For us he was never American. He was always the “old wise man in the village.” You had a problem? You would go to him. It doesn’t matter what you try, Ellington has been there!

With Monk, it was really a very unique experience. We flew into New York and I had heard that he was playing, so I decided to see if I could meet him.

Al Davis: Okay.

Abdullah Ibrahim: So they managed to get me backstage with his musicians and some other people… And Monk! I went up to him and I introduced myself, I said “I’m from South Africa and I’ve been inspired by your music. Thank you so much.” And he looked at me quizzically and walked to the other side of the room. Well, I’d heard about Monk and how he reacts. [Ibrahim laughs] But he came back to me several times and then went back again to the other side, and then he came and he said to me, “You are the first piano player to tell me that.”

Al Davis: Interesting!

Abdullah Ibrahim: Yeah! And I was a bit taken aback, but then I realized that there were so many musicians that I had met that were very negative about Monk, saying that he couldn’t play, that he had no technique. But I immersed myself in his music at that time.

Al Davis: Did you get a chance to spend time with Ellington?

Abdullah Ibrahim: Absolutely. We met in Switzerland, in Zurich. They used to come through every year on the tour and I would spend time with Ellington. It was an honor to spend time with the master. I had a lot of questions to ask, mostly not about music. One night, we spoke about water.

Al Davis: Okay…

Abdullah Ibrahim: Because he had composed a ballet, about water. He said to me, “The stones of the lake, the meander of the river, and the sea.” He took one drop of water and I think he created a ballet… but I don’t know if it’s ever been presented. [Ed.: This concept later became Ellington’s “River Suite,” which is still part of the Alvin Ailey repertoire.]

Va Lynda Robinson: I know that you studied at Juilliard in your early days in New York, but you also interacted with many of the progressive musicians like Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, Cecil Taylor and Artie Shaw. Tell me about that.

Abdullah Ibrahim: Those were vibrant days in New York. An era of liberation. We felt the need to upgrade some of the music and make it more relevant for the people. This is the beauty of the genre of music that we play because there’s always something that comes along and it makes it move in another direction. At that time it was quite incredible. They had those lofts in downtown Manhattan, where we could play until daybreak. Ornette would keep a place we could play 24 hours a day.

Al Davis: I was wondering, all the years you’ve been performing, do you see a difference in your audience now? Younger, older?

Abdullah Ibrahim: A lot of young people, about 60-70%. We have young musicians coming backstage all the time. That is what is quite enthralling. The youngsters stay engaged. Everything changes. So you have to adapt.

Va Lynda Robinson: Many of us older folks know you for “ Mannenberg,” which became a notable anti-apartheid anthem. How do you feel about that song’s legacy?

Abdullah Ibrahim: When we recorded this, we had no thought what it was going to be. We were in Cape Town, some younger musicians and I. We had four or five songs to do. We’d done two and we had break. I was playing a grand piano, but when we took this break I saw the little upright piano sitting in the corner. I played it, and it had this strange sound. And what they used to do in that township, is put thumb tacks in the hammer of the piano. It gets this metallic sound.

And so the first notes I played were [Ibrahim sings]. I called my musicians over from coffee, and we figured it out in about 17 minutes, when the engineer said to us, “Come and listen to this recording,” and we were pleasantly surprised. Because we realized that we had captured the music that we wanted to play, traditional music.

Always, when you were recording, engineers would suggest or tell you what to play. And this was us.

Well, when we took this recording to all the record companies nobody wanted it. But I had a friend who had a smaller record shop in Johannesburg. It was at the at the bus terminal, so it was bustling with people. We played it on the speakers of the shop and we sold 20,000 copies. It was a true shock. But it was the sound of the community, and what was happening in the community. Then it was played everywhere.

Va Lynda Robinson: It became an anthem.

Abdullah Ibrahim: Exactly.

Al Davis: Well it’s been great to talk to you, Abdullah Ibrahim! We’re looking forward to your show, which is at the Berklee Performance Center on November 16th. Music like this keeps us strong and keep us together. So we really appreciate this so much.

Va Lynda Robinson: Thank you.

Abdullah Ibrahim: Well, thank you so much for listening. Thank you!

Original article written by Al Davis on GBH